Imagine a long winter evening stretching ahead of you – in a world without electricity. You have the light from the fireplaces that you use to heat your home but it is dim. It will cost you money to burn candles or oil lamps; and gaslights, while beginning to be common for lighting streets and public buildings, will not gain wide acceptance for use in private residences until the 1850s. If you are to spend the money for lighting, how will you and your family entertain yourselves for the hours to come? Around the open fires of homes throughout history, but mostly lost today in favor of video games, TV, and streaming video, existed a solution: The parlor game.

Indoor games for groups are as old as history. From ancient Mesopotamia onward, people have enjoyed gambling on dice or card games and playing games of strategy to pass the empty hours. In England, Francis Willughby’s Volume of Plaies (1665) describes the rules of backgammon, and gives instructions for card games, beginning with the very manufacture of the cards themselves: take “3 or 4 pieces of white paper pasted together and made very smooth that they may easily slip from one another, and be dealt & played.”

By the Georgian period, 1714 – 1830, things had changed to the point where you did not have to manufacture your own cards. There were entertainments considered proper for ladies, those proper only for men, and others considered proper for both sexes. In this article, we are going to look at those that might be enjoyed by family and friends within your own walls.

Entertainments with Cards and Dice

Commerce is an 18th-century card game akin to the French Thirty-one and perhaps an ancestor of Poker. It was popular in the later 18th and early 19th centuries, however, some writers have indicated that it was most popular with the older set during the Regency era. This game has many of the aspects of modern Poker including scoring using pairs, triples, straights, and flushes.

Cribbage was invented in the early 1600s by Sir John Suckling, an English courtier, poet, gamester, and gambler. It derives from the earlier game of Noddy. Originally, the five-card game was played where each player only discarded one card to the crib. The goal of the game is to be the first player to score a target number of points, typically 61 or 121. Players score points for card combinations that add up to fifteen, and for pairs, triples, quadruples, runs, and flushes. Following the rules of game etiquette was important, and players followed them closely in cutting, dealing, pegging, playing, and using terminology. Some accounts contend that for many centuries, Cribbage was the only card game that could legally be played for money in English pubs.

English settlers brought the game to American shores where it became popular, especially in New England. Requiring only two players, it was readily adopted by sailors and fishermen as a way to wile away the time. Cribbage boards, which have either 61 or 121 holes, were crafted from a variety of materials and could be amazingly unique and elaborate in form and style.

Faro originated in France in the late 17th century. First known as Pharaon, it became extremely popular in Europe in the 18th century. With its name shortened to Pharo or Faro it continued to be widely played in England during the 18th and 19th centuries. The game was easy to learn, quick to play, and, when played honestly, the odds for a player were the best of all gambling games. In the early 19th century, it made its way to America where it caught on rapidly with the masses and became the most popular game in the gambling halls of the American westward expansion.

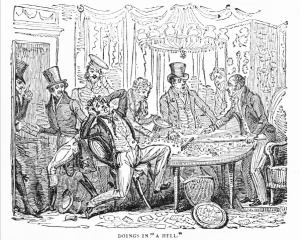

Hazard is an early English game played with two dice; Geoffrey Chaucer mentions it in his 14th century Canterbury Tales. Despite its complicated rules, hazard was very popular in the 17th and 18th centuries and was often played for money. During the Georgian era, Gentlemen played hazard for high stakes in English gambling rooms, especially at Crockford’s Club in London. In the 19th century, the game craps developed from hazard through simplification of the rules. Hazard spread from England to France and later to the United States where the simpler Craps eventually supplanted it.

Loo, (Lanterloo) is supposed to have reached England from France, most probably with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Other researchers indicate it may have been brought to England from Holland. Whichever way it may have come, by the turn of the eighteenth century it was already England’s most popular card game. The idle rich of that time considered it a great pastime, but it got a very bad reputation as a potentially vicious “tavern” gambling game during the nineteenth century.

As an interesting historical note, Alexander Pope mentions Loo in his poem, The Rape of the Lock: Canto 3.

Piquet has long been one of the all-time great card games and is still played today in some quarters. The first written mention of the game dates to 1535. The game began in Germany during the Thirty Years War, and first became popular in England after the marriage of Queen Mary I of England (Bloody Mary) to King Philip II of Spain in 1554. During this period the game was known as Cent, after the Spanish game Cientos, referring to the fact that one of the chief goals of Piquet is to reach 100 points. Following the marriage of King Charles I of England to Henrietta Maria of France in 1625, the British adopted the French name for the game.

Piquet remained the foremost two-person game throughout the 18th century, eclipsing even Cribbage. Edmond Hoyle, after the success of his Short Treatise on Whist in 1743, turned his attention to Piquet in the following year. One of the principal centers of Piquet play, as well as card-play in general was at Bath. Here, England’s landed gentry won and lost large sums, indeed fortunes, as both bystanders and players.

In America, Piquet was just as popular. In 1753, William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin, penned the following “love” poem from his bachelor group, to a group of young ladies that were summering in Horsham, to the north of Philadelphia.

Sometimes we kill a tedious hour,

We venture at piquet

Yet even there we feel your pow’r

and know not how to Bett

For Cupid laughs at our mistakes

We lose our money for your Sakes.

Vingt-et-Un is an early version of Blackjack that has not changed much since Regency times. Like modern Blackjack, Vingt-et-Un does not require partners and, if a man can keep track of cards, read his opponents well, and is brave enough to double down; the play can be tense and exciting. While there are disputes about its origin, it is certainly related to several French and Italian gambling games. One variant, often played in England, is called Pontoon, which differed from Vingt-et-Un mainly by using a different deck than the “standard” English deck. This deck can be simulated today by removing the 10 spot cards from the deck. Thus, the card values run: A,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,J,Q,K.

Whist descended from the 16th century game of Trump or Ruff. Whist replaced the popular variant of Trump known as Ruff and Honours. The game takes its name from the 17th Century usage of the word whist (or wist) meaning quiet, silent, attentive, which is the root of the modern wistful.

According to the Hon. Daines Barrington, Whist was first played on scientific principles around 1728, by a party of gentlemen who frequented the Crown Coffee House in Bedford Row, London. Edmond Hoyle, who is believed to have been a member of this group, began to tutor wealthy young gentlemen in the game, and published A Short Treatise on the Game of Whist in 1742. It became the standard text and rules for the game for the next hundred years and led to the game becoming fashionable.

Entertainments Played on a Game Board or Table

Backgammon is a popular recreational pursuit for millions of people throughout the Four Corners of the globe, and the people of the Georgian period were no different. One can make a good argument that the periodic printing of new texts devoted to various recreational games provides an accurate indicator of their popularity. From this premise, one can show that backgammon was one of the most popular parlor games of the British literate classes until the latter half of the 19th century.

In America, Backgammon boards were popular among the wealthy by the 1770s, and the lower sorts, at least the men, could indulge in such recreations at the ubiquitous public taverns and coffeehouses. One writer singled out what he considered the distasteful and vile practice of New York’s tavern life:

“I mean that of playing backgammon (a noise I detest) which is going forward in the public coffee-houses from morning till night, frequently ten or a dozen tables at a time.”

Billiards are generally accepted as having evolved from a game, played outside on a lawn that was like croquet. Play moved indoors to a wooden table with green cloth to simulate grass, and an edge placed around the table to keep the balls from falling to the floor. In these early years in England, the balls were shoved with wooden sticks called “maces” and not struck.

During the 18th century, the game of billiards became part of the lifestyle of the “average person.” In England, the public played billiards regularly. This was particularly true in London, but later expanded across the countryside as billiards became a part of life in the inns and coffeehouses, as well as the occasional “chocolate” house.

Major Regency figures, George IV (the Prince Regent and later King) and the Duke of Wellington both owned tables and were known to be fond of the game. Meanwhile in North America, there is a record of billiards as early as 1709 when a William Byrd was recorded as playing billiards at his home, mornings, afternoons and evenings. In addition, according to John Richard Alden, in his biography of George Washington, our first President was a billiard player, at least as a young man.

Chess history spans over 1500 years. The earliest predecessor of the game probably originated in India, before the 6th century AD, and spread from there to Persia. When the Arabs conquered Persia, the Muslim world took up chess, which then spread to Southern Europe. In Europe, chess evolved, during the 15th century, into roughly its current form.

Chess was well established and popular, particularly among the upper classes and the educated during the Georgian period, the Normans having introduced it to England around the time of the Invasion. The first London and Paris chess clubs were formed in the 1770s and, as the 19th century progressed, chess organizations developed quickly. There were correspondence matches between cities, such as when the London Chess Club played against the Edinburgh Chess Club in 1824.

Dissections, later known as jigsaw puzzles, first appeared around 1760 when John Spilsbury, a London engraver, made the first one. Spilsbury mounted one of his maps on a sheet of hardwood and cut around the borders of the countries using a fine-bladed marquetry saw. The transition from “Dissections” to “jigsaw puzzle” occurred slowly. The jigsaw, originally a “powered fretsaw,” came into being sometime in the 19th century. Researchers have not seen the word jigsaw on any puzzle made in the 19th century. Thus, the use of the title “dissection” continued thru at least the early 1800s. Spilsbury’s original intention, to use them to teach geography to English schoolboys, blossomed far beyond schools since many people found the pastime to be entertaining.

Draughts (pronounced “drafts”), today known as Checkers, is one of the oldest games known to man. Its history dates to the very cradle of civilization, where remainders of the earliest form of the game were unearthed in an archeological dig in the ancient city of Ur in southern Iraq. This version used a slightly different board, which was carbon dated at 3000 B.C. A similar game, using a 5×5 board, existed in ancient Egypt as far back as 1400 B.C.

In 1756, an English mathematician, William Payne, wrote a treatise on draughts. Now, with its own written rules, the game settled in England where the game steadily rose in popularity as the years went by. By the later years of the Georgian era, you could find the game in every tavern, coffee-house, and many private homes.

Fox and Geese appeared in the 14th century and quickly became popular all over Europe. We know many variations of this originally Germanic and Celtic board game called “Tafl.” In Britain, it became known as “Fox and Geese”, “Renard et les poules” in France, “Lupo e pecore” in Italy, “Fuchs und Gänse” in Germany, “Rävspel” in Sweden, and “Schaap en wolf” in Netherlands.

The Game of Goose reached England by 1597, when John Wolfe entered “the newe and most pleasant game of the Goose” in the Stationers’ Register on June 16. The game apparently became and maintained its popularity since, in 1758; the Duchess of Norfolk planted a Game of Goose in hornbeam at Worksop, as mentioned by Horace Walpole. Such hedge designs were at the time popular among the European gentry, although instead of the Goose game’s spiral, most were laid out as living Labyrinths, like the famous maze at Hampton Court.

In Part 2 of this article, we will continue our investigation of Georgian era entertainments with a look at Parlor Games and other forms of indoor entertainment.

Chuck H

(c)2014

[…] Part 1 of this post we looked at how the people of the Georgian era entertained themselves indoors using […]

LikeLike

[…] THE HISTORIC INTERPRETER https://historicinterpreter.wordpress.com/2014/11/11/entertainment-in-the-georgian-era/ […]

LikeLike

[…] Entertainment in the Georgian Era […]

LikeLike